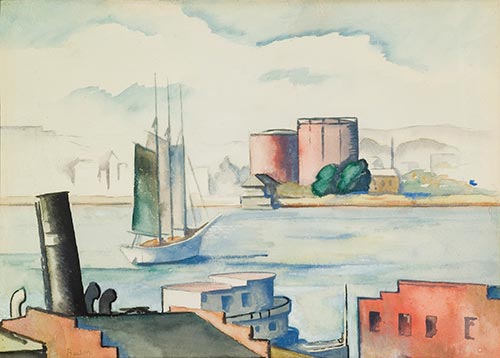

Harbor Scene

Written by Dr. Henry Adams, author of “Thomas Hart Benton: An American Original”

This is undoubtedly one of the watercolors that Benton made in the Navy, while stationed at Norfolk, Virginia and it will be included in my catalogue raisonne of Benton’s work.

In 1918, to avoid being drafted in the infantry, Benton used family influence to get a position in the navy, safely off the battlefield. In September 1918, after being trained to understand naval signaling, and spending some time shoveling coal, he was assigned to the naval base in Norfolk, Virginia, where he made descriptive drawings of boats and construction projects for record-keeping purposes. Benton spent two days a week gathering information with a photographer and was supposed to spend the next three days finishing his sketches, but since he could finish his drawings in less than an hour this left him a substantial amount of time for his own work. During the latter part of his stint in the navy he was even permitted to live off base in a Norfolk lodging house. In December 1918, Charles Daniel staged an exhibition of Bentons’ Navy watercolors at his gallery in New York, which received excellent reviews both in The New York Herald and The New York Times.

Several of Benton’s navy watercolors can now be located, four of which have elements similar to Harbor Scene. The general composition of this piece is particularly similar to Sailboat, a view of an anchored three-masted sailing ship with buildings in the background, which once belonged to Benton’s early patron, Dr. Alfred Raabe. While Sailboat has been traditionally dated to 1912, it most likely is a Norfolk watercolor from 1918 and may well have been made from almost the same vantage point as this watercolor.

Three other navy watercolors repeat individual motifs found in Harbor Scene. For example, Ship with Figures and Tree, 1918 (private collection) records a three-masted ship somewhat similar to the one shown here, although with a different rig. Tugboat at the Wharf (private collection) records a tugboat that resembles the one shown here, with a similar sailing vessel behind it. Norfolk Landscape, 1918 (private collection) contains a cylindrical storage tank similar to the ones that appear in the background of this watercolor.

While not chiefly remembered as a watercolorist, Benton had an exceptional talent for this medium. He established the basic features of his watercolor style in 1907-08, when he attended the Art Institute of Chicago and was the star student in the watercolor class of Frederick C. Oswald (sadly, none of Bentons’ classroom watercolors seem to survive, but some watercolors he made around 1912 seem to be fairly close in technique to his Chicago work.)

While studying in Chicago, Benton learned to make watercolors rapidly and directly, with bold colors reminiscent of Impressionist or Post-Impressionist paintings (including the use of blue shadows). In addition, after seeing an exhibition of Japanese prints from the collection of Frank Lloyd Wright, he became interested in dramatic patterns, in the interplay of figure and ground, and in the use of evenly gradated tones of color in areas such as the sky.

While executed some ten years later, this Harbor Scene watercolor capitalizes on many of these techniques. The execution is forceful and direct, and the colors bold. Shapes are often created through the clever articulation of figure-ground relationships, notably in the case of the background buildings, which are defined by the pattern they make against the sky. Flat color areas, such as the walls of the buildings, are played against areas with gradated colors, as in the sky and water. Benton’s pattern making skill becomes evident when we study forms that are similar, such as windows, and note how he expresses them in different ways, often evoking the shape by outlining only a small part of the overall form.

What distinguishes the Navy watercolors from Benton’s early work is a greater interest in rhythmic relationships of three-dimensional form. As a group, the Navy watercolors vary somewhat in their style, ranging from a Cubist-Futurist approach, probably inspired in part by the work of John Marin, to a somewhat more straightforward realism, as in this example. But even the more realistic, closely observed examples, organize geometric shapes in a way which leads the eye through the composition in rhythmic pathways, such as the line of visual movement in this watercolor which runs from the smokestack of the tugboat to the three-masted vessel to the storage tanks in the background.

Benton himself attached great importance to these navy watercolors. As he later wrote in his autobiography, An Artist in America (4th revised edition, pages 44-45):

This was the most important thing that, so far, I had ever done for myself as artist. My interests became, in a flash, of an objective nature. The mechanical contrivances of building, the new airplanes, the blimps, the dredges, the ships of the base, because they were so interesting in themselves, tore me away from all my grooved habits, from my play with colored cubes and classic attenuations, from my aesthetic drivelings and morbid self-concerns. I felt for good the art-for-art’s-sake world in which I had hitherto lived.

I had found that it was not necessary to look into myself and my “genius” to find interesting things. I had found that these things existed in the world outside myself… I was released from the tyranny of the prewar soul which everybody so assiduously cultivated in the world of art and which was making of it such a precious field of obscurities.

Harbor Scene has an interesting provenance, since it was once in the collection of Glenn C. Janss, who was involved in the creation of the famous ski resort at Sun Valley Idaho, and who assembled a notable collection of American art. In 1986 the Janss collection was the subject of a traveling exhibition organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and this piece was reproduced in a full-page, full-color illustration in that catalogue. The full reference is: Alvin Martin, American Realism from the Glenn C. Janss Collection, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in Association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., publishers, New York, 1986, plate 206.